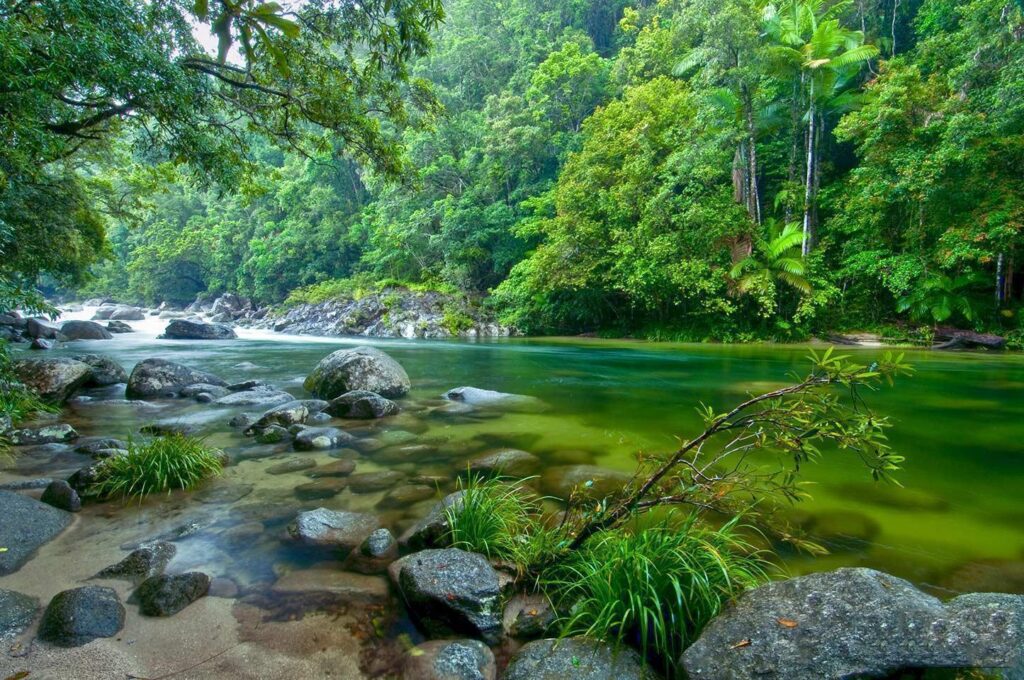

November 30th 2023 will mark the 40th anniversary of the Daintree blockade protests,

which paved the way for World Heritage status of the Daintree Rainforest.

I recommend watching the feature length documentary below “Earth First”, I have remastered this video footage from a VHS copy to digital with some noise and colour filters applied, please enjoy and share for educational and preservation of this truly historic and important event in the history of Australia.

The Daintree Blockade was a significant environmental protest that took place in 1983. It was a 10-month-long demonstration led by local residents to prevent the bulldozing of native forest for a new road north. The protest played a crucial role in raising awareness about the Daintree Rainforest and the importance of preserving it. The Daintree Blockade is considered one of Australia’s most iconic environmental protests.

The battle for the Wet Tropics

How Queensland’s Daintree rainforest was saved – ABC News

In 2018, it’s hard to imagine that until three decades ago, the Daintree rainforest was seen primarily as a timber plantation by the governments of the day. (Note: 40 years now at time of writing! crazy hey! Lets save this planet people! 🌻🌴🤓🌳🌷)

The Wet Tropics Area includes:

- Almost 90,000 hectares

- 135 National Parks

- More than 700 protected areas

- Just under 400 bird species (11 of which are unique to the region)

- More than 100 different reptiles

- 90 species of orchids

After years of controversy, Queensland’s Wet Tropics were inscribed on the World Heritage list on December 9, 1988, largely halting development, logging and human interference.

The story of how the protection of a 600-kilometre stretch of living ancient history was achieved is one of political agendas, death threats and protests.

It also marked the end of Far North Queensland’s timber industry and the beginning of a new industry in the region — ecotourism.

Thirty years on, some of the key proponents to achieving the UNESCO listing have recalled the struggle.

Silly Threats

Today, Dr Rosemary Hill is a CSIRO research scientist in land and water and an adjunct associate professor with James Cook University.

In the mid-1980s, she was a self-professed ‘greenie’, who helped to start the Cairns and Far North Environment Centre (CAFNEC), a grass-roots conservation council advocating for the protection of the tropics.

But it was her personal safety that became cause for concern when she received a series of death threats.

“I had people come into the office to give me a death threat. I had people leave notes in our letterbox,” Dr Hill recalled.

“The Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, came to a public meeting, got up and said, ‘These greenies should be tarred and feathered and run out of town’. That was threat to all of us.

“So, as well as these personal threats, there was almost this incitement to violence from our political leadership, which was really unacceptable.”

Dr Hill chose not to publicly acknowledge the threats she received at the time.

“You just dust it off, you don’t publicise it, because the issue then becomes that they gave you a death threat and that’s not what we were there for.”

‘It was like walking into an ants’ nest’

In 1988, Peter Hitchcock was appointed as the first executive director of what was to become the Wet Tropics Management Authority.

He said he held grave concerns about the political agendas at play after the advice he received from a then state government minister.

“He told me in no uncertain terms, ‘You won’t last in the job. No-one wants the World Heritage Area. You’ve got no chance of success’,” Mr Hitchcock said.

“It was like walking into an ants’ nest that had been stirred up.

“[It] was a real kick in the shins thinking I was enthusiastically going off to this job and I was being told by the Minister that it was a hopeless situation and that they [local landowners] would run me out of town.”

When he began working from Cairns, Mr Hitchcock said he found the mood locally was very different.

“The majority of the private landowners I had to deal with that were in the World Heritage Area were supportive,” Mr Hitchcock said.

“Mostly it was people lacking information, asking, ‘Where’s the boundary? Where is this World Heritage Area? Where’s the map?’.

“So at last people could walk into my office and ask for the map.”

The fight for Indigenous voices to be heard

While both sides of the debate were arguing their opinions on the Wet Tropics Area, the region’s Indigenous groups say their voices were largely ignored.

Allison Halliday, of the Malanbarra clan of the Yidinji tribe, recalled her people’s concerns.

“We weren’t necessarily against the listing, but we were worried about the fact that it was only listed for natural and scenic values and not cultural values,” Ms Halliday said.

“It had no regard for Aboriginal people and the cultural values we have attached to the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area.”

Ms Halliday said the region was home to 18 Aboriginal rainforest tribal groups who made a symbolic stand, burning a copy of the original World Heritage agreement.

“It was raining and we wanted to do it the traditional way; however, because of the rain we couldn’t actually make a fire so we ended up using a lighter to burn the plan.

“It took 25 years before we actually got cultural values attached to it.”

‘Everyone thought we were crazy’

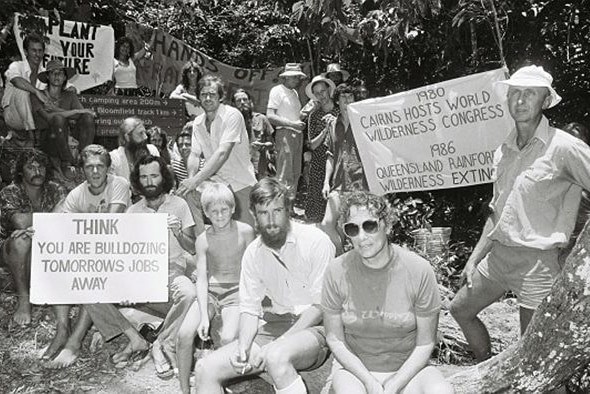

It was an earlier protest that put both the Daintree and the notion of World Heritage listing of the Wet Tropics on the national agenda.

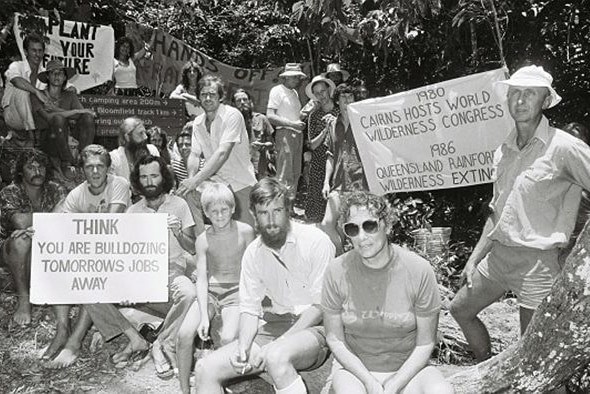

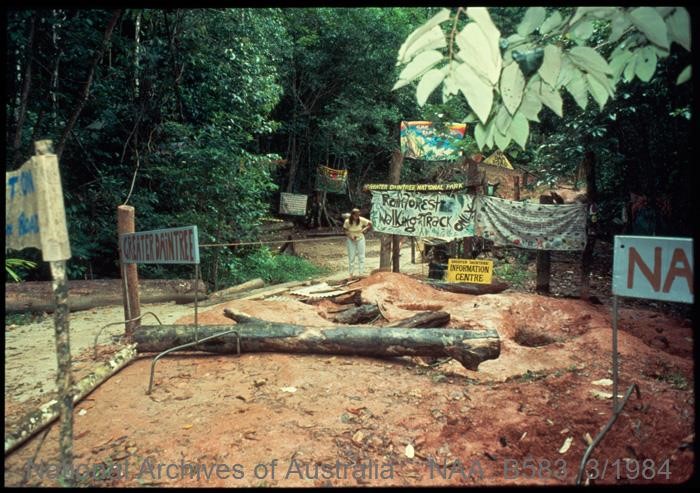

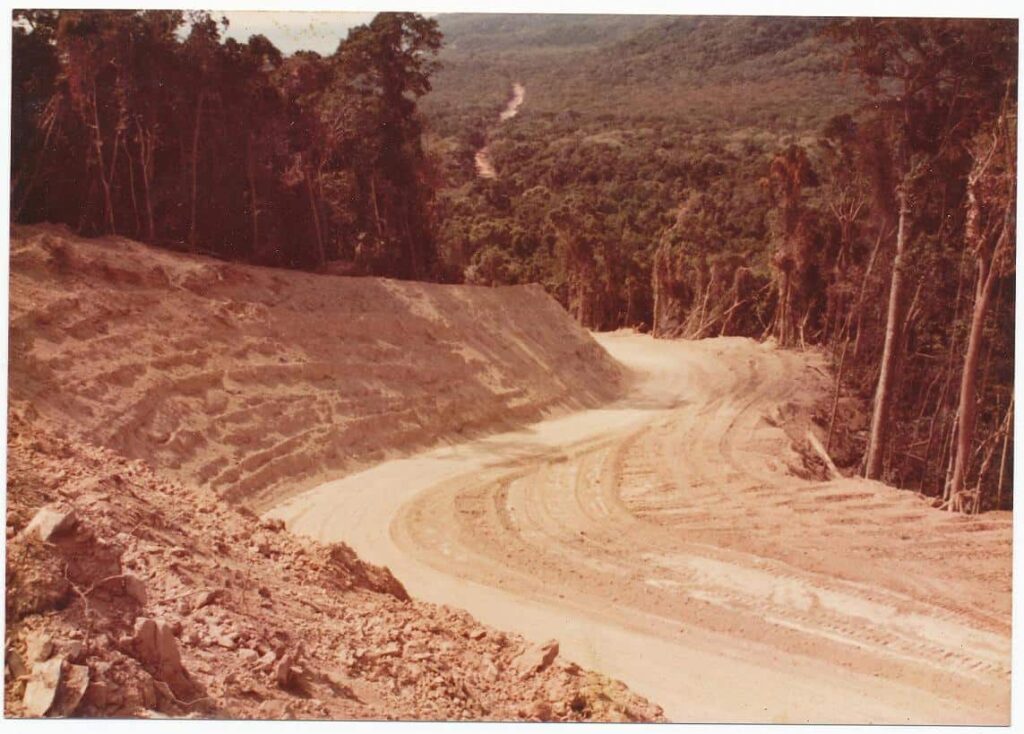

In 1983, five years prior to the UNESCO agreement, local residents staged the Daintree Blockade, a 10-month protest to prevent the bulldozing of native forest for a new road north.

Carpenter-turned-conservationist Mike Berwick was arrested as a protester in 1983. Eight years later he became the mayor of the region’s Douglas Shire Council, a position he held until 2008.

In that time, the region began to thrive as a world-famous ecotourism destination, valued for its natural heritage rather than its extraction potential.

“No-one imagined the scale to which it [would] grow and that you’d end up with half-a-million visitors a year coming to the place; it looks obvious now but back then it was beyond people’s comprehension,” Mr Berwick said.

“Tourism in those days was the Gold Coast, it was high rises on the beach, so everyone thought we were crazy, but we thought it was beautiful and we assumed everyone else would too and we were correct.”

But in part due to this multi-billion-dollar success, Mr Berwick said the challenges the Daintree faced today were alarmingly similar to 30 years ago.

“The current Federal Government is now wanting to spend money on developing it, advocating a main road through to Cooktown, the very thing we fought back then.

“The Government should be investing money into its conservation before they invest money in developing it, this is nuts.

“If we put a highway through here to Cooktown, that’ll mean putting a bridge over the Daintree, widening the road over the Alexandra Range. It’ll change the face of this place forever.”

Source and credit for above to: Brendan Mounter and Phil Staley [ABC Far North]

“The single biggest threat to our planet is the destruction of habitat and along the way loss of precious wildlife. We need to reach a balance where people, habitat, and wildlife can co-exist – if we don’t everyone loses … one day.” – Steve Irwin (R.I.P M8!)

“This is the third day I will have spent buried up to my neck with my right arm chained between two logs. The logs are in turn part of a fiddlestick combination linking my hole with Graeme Platt’s…Last minute preparations complete, we entered our holes to await the arrival of the police. I felt a strange serenity. There was no fear in waiting, rather a calm understanding that this was the right action and stood above the law of the land.” – Graeme Innes describing being buried to prevent bulldozers from clearing sections of the Daintree Rainforest in 1984

A decade ago… what have we learnt as a planet? Lets make some change people! We need to act now, recycle, reduce waste, push for change, educate others!

🌻🌴🤓🌳🌷🐨🐞🐝🐠🐬🌍

30th anniversary of the Daintree blockade – ABC (none) – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Former Greens leader Bob Brown says he was exhausted by the Franklin blockade so he decided to take a holiday up in the Daintree.

“As part of rest and recreation I decided I’d go up there, but wouldn’t get involved – mistake – to go to the Daintree was to get involved,” he said.

Mr Brown says he explored the rainforest, heard stories from locals and decided to help raise awareness.

“I knew the environment minister in Canberra, so I flew to Canberra … and went to see Barry Coen, the Minister for the Environment, about the Daintree,” he said.

“He put his hands up as I was coming in to the room … he waved his hands in front of his face and said ‘I’m not going to talk to you about the Daintree’,

“So I said ‘well Barry, you just sit there, I’m going to talk to you about the Daintree’.”

Mr Brown says he saw the pressure the conservationists in the Daintree were under and says the rainforest’s fate depended on federal action.

“The shear energy and commitment of those campaigners on the ground – that was core to saving the Daintree itself,” he said.

“The public responded to that, so did other politicians, so did other campaigners like myself, but it goes right back to those folks campaigning,

“They really can proudly feel these days that they saved the Daintree.”

Listen to the audio on the right for the full interviews and radio excerpts from the time of the blockade.

Former Douglas Shire Mayor Mike Berwick was a spokesperson for the protestors and recalls the trials and tribulations of the 10-month protest.

“We had been talking to the council and the council was kind enough to us, they had listened politely, but took no account of us, they thought we were a bit ‘off with the fairies’ I suppose,” he said.

“So they finally resolved in council that they were going to start this road, there was no real planning to it, they were just going to send a bulldozer through and find their way through the scrub and come out at Bloomfield.”

Mr Berwick says the first protest was very much a local affair.

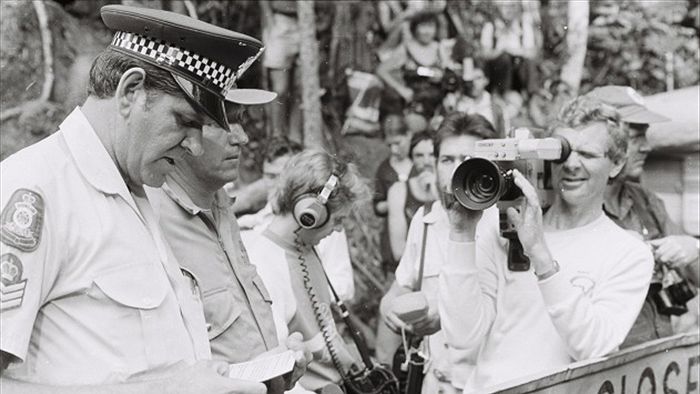

“That was all locals in 1983 that went up there and protested, it was the local people and the local cops and the local bulldozer driver, who all knew each other,” he said.

“It was a protest, it was a theatrical event and it was designed to attract attention to the plight of the rainforests in north Queensland.”

Mr Berwick says the protesters were well organised and set up live interviews between protestors in trees and Sydney radio programs.

“What we had already done in our preparation, was we’d put a yacht out at low isles with people living on it and we had a repeater station,” he said.

“So we had a direct line to low isles and a direct line to a licensed radio facility in Mowbray and we had the best communications on about 1 watt and the coppers had hundreds of watts and couldn’t get their messages out.”

Mossman resident and author Bill Wilkie was 12-years-old at the time, but has developed an interest in it and is writing a book about the history of the Daintree blockade.

“I moved up here to the area about eight years ago and heard stories about the blockade, about the hippies up trees, lying in front of bulldozers,” he said.

“It was kind of a bit of a mythology of the shire, where everyone would talk about it, and know about the rumours and have heard the stories, but some of the facts were a little bit allusive as to what actually happened,

“I thought that there was a bit more of a story than the general public knew about and about four years ago I started the process of writing the book.”

Mr Wilkie says for 40-50 years the local shire had wanted to build a road through the Daintree.

“The tyranny of distance had really prevented that part of the world from developing,” he said.

“In the 70’s people who were environmentally conscious if you like, and conservation minded began moving to the area as well,

“Once they got there they were looking to conserve it rather than develop it.”

Mr Wilkie says the protestors were no match for the power of the local and state governments.

“It took one day for the initial blockade to be pushed through and then another couple of weeks while the council negotiated around some people that were in trees further down the road,” he said.

“The numbers just never really showed up like they had for the Franklin campaign and in the end … there were simply not enough protestors to maintain the protest,

“The protestors really ran out of people who were willing to be arrested … so within 2 or 3 weeks that 1984 protest was abandoned as well.”

Source: 30th anniversary of the Daintree blockade – ABC (none) – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Daintree Rainforest is estimated to be 130 million years old which is tens of millions of years older than the Amazon Rainforest. This natural wonder is home to thousands of species of birds and other wildlife including 30% of Australia’s frog, reptile and marsupial species in Australia, 65% of the country’s bat and butterfly species as well as 18% of all bird species. 12,000 insect species can also be found right here in the Daintree Rainforest.

In 1983 the Douglas-Shire Council pushed ahead with a controversial plan to construct a permanent road from Cairns to Cooktown which was supported by the Bjelke-Peterson State Liberal Government. The publicity generated by the 1983-84 community blockade provided a turning point in the campaign to protect Queensland’s tropical rainforests.

In 1988, the Hawke Federal Government listed the Wet Tropics Rainforests as a World Heritage Area. Due to its constitutional powers relating to international agreements, the Federal Government was able to overrule the Queensland State Government.

While the World Heritage Area included the majority of the upland areas of the Daintree Rainforest, it excluded most of the hill faces and coastal lowlands. Ten years prior to the World Heritage listing, large sections of the lowland rainforest were subdivided for residential development by a Cairns property developer.

Originally there were 1,100 subdivided blocks of land. Many were not built on because there is no bridge over the Daintree River (access is by ferry) and no mains electricity. However, developers have left a legacy of freehold properties in the heart of the Daintree Lowlands surrounded by the National Park and the World Heritage Area and these properties are now being steadily developed.

Various attempts by governments have failed to solve the problems created by the residential subdivision. In 1984 the Federal and State Governments funded the $23 million Daintree Rescue Program to be implemented over four years. This was successful in purchasing a number of significant blocks of land for inclusion in the Daintree National Park, as well as developing eco-tourism infrastructure. However large amounts of critical conservation land was still not protected.

Prior to the 2004 election, the Federal Government committed $5 million to the Daintree; however, this was largely diverted to landholder education rather than the much-needed buy back.

In June 2004 the Douglas Shire Council implemented a 12-month moratorium on approval for development in the Daintree while it prepared a Douglas Shire Draft Planning Scheme for the area. Fortunately, the Queensland State Government (again immediately prior to the 2005 State Election) also committed $5 million and following the adoption of the Scheme in 2006 committed another $5 million.

The Douglas Shire Council Planning Scheme protects 350 properties north of the Alexander Range, which have been acquired with Queensland Government funds. The Scheme also created “Rainforest Residential and Rainforest Tourism Precincts” where development is allowed and will be concentrated. Properties with building permits obtained before the adoption of the Scheme also retained these rights. Therefore development can still proceed north of the Alexandra Range including at Cow Bay, Diwan, and Cape Tribulation. Land south of the Alexander Range remains unprotected by the Scheme and development proceeds unchecked.

Rainforest Rescue works to purchase and protect those properties containing intact high-conservation value rainforest which still maintain their development rights. Our vision is to purchase all remaining rainforest properties by the year 2040.

Both the State and Federal Governments have indicated that they have no intention of funding further buy back schemes in the Daintree.

Bill Wilkie is a Mossman based author currently writing on a book about the Daintree Blockade. Purchase his book at www.facebook.com/daintreebook.

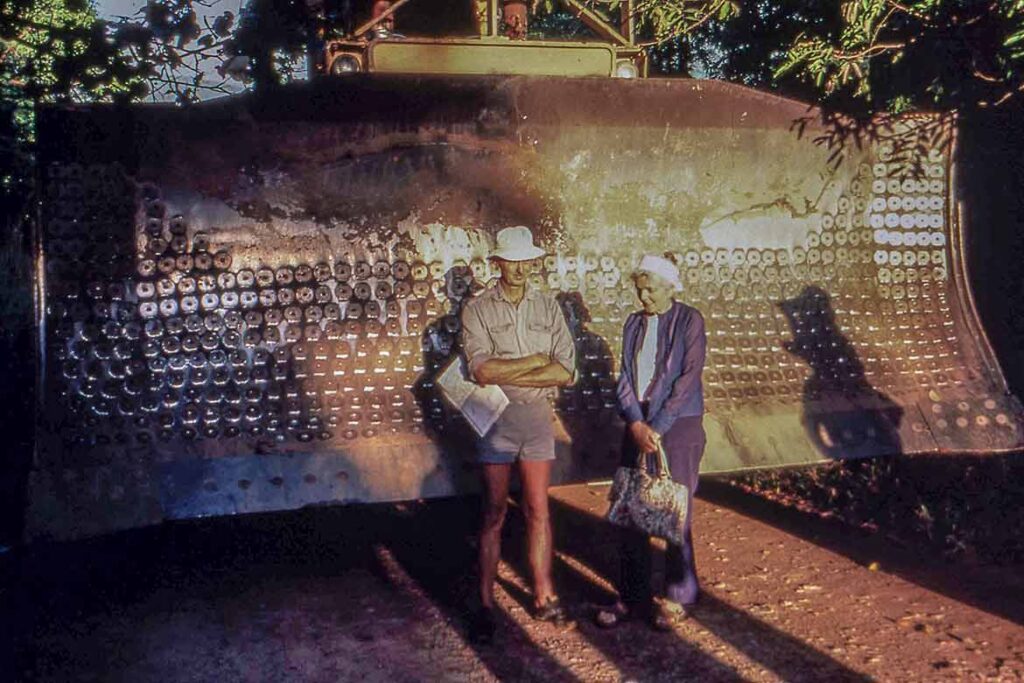

To prevent people from destroying the coast at Cape Tribulation in 1982 a group of eight residents, many of them members of the Cape Tribulation Community Council (CTCC) took matters into their own hands. They were concerned about the degradation of the delicate rainforest bordering the beach resulting from people chopping down trees and saplings for firewood and tarpaulin frames, lighting fires on buttress roots and holding car races up and down the beach.

The local residents visited all the campers on the beach one Thursday morning and told them they would be erecting a barricade at 3pm, after which there would be no further access.Using a tractor they dragged abandoned car bodies to form the barricade, blocking beach access. Previous barricades erected by Council had been cut through with a chainsaw and removed. The CTCC circulated a brochure for visitors outlining the unique ecological features of the area and asking people to respect the natural environment.

Degradation the beach was just one of the CTCC’s many concerns: subdivision of large rural blocks with inadequate planning;plans for resort developments inconsistent with the natural surroundings; talk of a bridge over the Daintree River; and the ever present threat that many of these issues would be compounded by the completion of the Cape Tribulation to Bloomfield road, a rough track that had first been bulldozed through in 1968.By the early 1980s this track was gaining attention as a walking track with great tourist potential. The ‘new settlers’ of Cape Tribulation understoodthat the economic future of the area lay in the conservation of the Daintree coast, not just the development of it.

When CAFNEC was formed in March 1981 as an umbrella organisation for the many smaller conservation organisations across the far north, it took on many of the issues north of the Daintree River, including ‘the road’.Their concerns were well founded, for in 1983 Douglas Shire Council announced plans to build the road to Bloomfield, the so-called ‘missing link’ of highway along the east coast of Australia

CAFNEC commenced a campaign of letter writing, petitioning, lobbying politicians, including Douglas Shire Chairman Tony Mijo, and public awareness. From a film night and information session a local group, the Douglas Shire Wilderness Action Group (WAG), was formed to try and stop the road.Their lobbying efforts didn’t work, and as a last resort they planned a blockade.

When work commenced on the road it was a small group of local people who showed up to form a non-violent protest in an attempt to stop work. They reported feeling ‘small, helpless and green’.Through most of December of 1983 and then again in August of 1984 the protesters sought to stop the road going through. They lay in the path of the dozers, chained themselves to trees and pleaded with all levels of government.They failed to stop the road being built, but in staging the protest they gained the attention of the media, politicians and the Australian public. As public awareness changed, an opportunity arose, and the years of campaigning, mapping, developing a scientific case for conservation, and public education paid off.

It was individuals who barricaded the beach at Cape Tribulation, who formed CAFNEC and WAG and staged the Daintree protest, and who campaigned for a decade and finally achieved World Heritage listing for Queensland’s wet tropics. In doing so they not only protected the region’s rainforests, they changed the cultural and social landscape of the far north for generations to come. There is much to learn from their commitment, determination and foresight.

Unlike the audio recordings above, This "Radio Interview" Below is completely fictional and was AI generated by Microsoft Bing during my research of the Daintree Blockade. I thought it was fitting to include it here to show the contrast from the 1980's protests to the technology we now have in our hands today as I publish this in the Daintree Rainforest via Starlink satellite internet. Lets come together as a civilisation and use these tools and other resources to protect the environment and stop the impact of climate change. Tim.

# Daintree Blockade Radio Interview

# [Sound of birds chirping]

Interviewer: We are here today with a brave activist, perched high up in a tree, fighting for the preservation of the Daintree Rainforest. Can you tell us your name?

Activist: Greetings! I am Gummy, a rainforest warrior, standing tall amidst the lush green canopy.

Interviewer: Gummy, what inspired you to take part in this blockade?

Gummy: The Daintree Rainforest is a treasure trove of biodiversity, home to countless species found nowhere else on Earth. It is our duty to protect this natural wonder from destruction.

Interviewer: How has the blockade been progressing so far?

Gummy: It has been a challenging journey. We have faced police heavy-handedness and witnessed council bulldozers tearing through the fragile ecosystem. But we remain resilient, united in our cause.

Interviewer: What message would you like to convey to our listeners?

Gummy: I urge everyone to recognize the importance of preserving our natural heritage. Together, we can make a difference and ensure that future generations can experience the wonders of the Daintree Rainforest.

[Sound of wind rustling through the trees]

Interviewer: Thank you, Gummy, for sharing your story and shedding light on the Daintree Blockade. Stay strong!

Gummy: Thank you for giving me a voice. Let our message echo through the treetops and inspire change.

[Sound of birds chirping fades out]